Author’s Notes

What happened next…

Lucie Mary

Lucie Mary Niven returned safely in June 1894 to London, Ontario, where she was welcomed by her father, brothers, and friends. Her brothers, Hugh and Knox, were young men now, eighteen and sixteen years old. Lucie helped her father in his surgery. They were a busy household, occupied and independent as they settled into life, glad to be together again. Lucie kept up her correspondence with her aunts and grandfather, faithful to her promises to keep them part of her life. She visited her Irish family in 1897 and did see her grandfather Thomas again. She also visited her father’s mother, Eliza Boomer Niven, in Lisburn at her home, Chrome Hill. Eliza died in 1900 and Thomas in 1901, just after his ninetieth birthday.

Lucie Mary and Shepherd Ivory Franz

Lucie made friends easily and kept them for a lifetime. As a result, she had a social life that took her into Canada’s society in London, Montreal, Toronto, and beyond. In 1901 her friend Edna Gartshore took Lucie along to Boston, where Edna was visiting her fiancé, Alex Cleghorn, who was teaching at Harvard Medical School. He, in turn, brought along a young assistant in the medical school, Shepherd Ivory Franz, a psychologist. A lifelong love and friendship began that evening.

The following year, on June 18, 1902, Shepherd and Lucie, twenty-seven, were married in London, Ontario, at St. Paul’s Cathedral. Her brother Hugh was their best man. Knox was also present. Both young men would eventually join Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry stationed in Edmonton, Alberta. Their units would be called to serve in World War I. Lucie and Shepherd started their married life in Hanover, New Hampshire, where he taught at the Dartmouth Medical School. Before settling in Hanover, they honeymooned in Dublin, where they visited the aunts, reinforcing a tie that remained important to Lucie all her life.

Marriage did not diminish Lucie. She was a strong partner to her husband, who encouraged her to be herself and develop her own world of interests. The Franzes’ first child, Theodora Niven, was born July 16, 1905. By that time Lucie and Shepherd had moved to a suburb of Boston, where he became superintendent of McLean Hospital. Much of the early psychological research was done in “insane asylums,” where subjects could be observed over a long period of time in many situations. Lucie was very proud of Shepherd’s early research on the function of different parts of the human brain and how they related to physical and psychological abilities. Psychologists from around the world visited, and she thrived on knowing them as people as well as academics and enjoyed her role as hostess and tour guide. Like her mother, Lily, she enjoyed entertaining and did it well.

Elfie came to visit in the spring of 1906 to meet her new great-grandniece. Her ship landed in New York, and she took the train to Boston, where Shepherd met her in his newly purchased automobile. Elfie wrote to Frances about Shepherd’s new auto, which cost $500 according to Lucie, an exorbitant sum. It was an open touring car, the 1906 Ford Model N Runabout. Shep was very proud of his fine car and quite new to driving. Elfie admitted in her letter to Frances: “Shep is, I suppose, a good driver, but I was terrified. I did survive to write this letter to you and was glad to have Lucie’s reassuring arms around me when we finally reached their home.” It was her first ride in an automobile. Theodora, known as Doedy, was a bright, inquisitive child, and Elfie was devoted to her during her stay and well beyond.

When Elizabeth Knox, my mother, was born September 23, 1910, the growing Franz family had resettled themselves in Washington, DC, where Shepherd assumed the post of superintendent at St. Elizabeths Hospital.

1911: Ireland

Lucie took her new baby, five-month-old Elizabeth, and five-year-old Theodora to Dublin in early 1911. It was Lucie’s plan to have Elizabeth baptized in St. Patrick’s Cathedral with her aunts in attendance. I can only imagine the discussion that must have preceded the decision to take that trip. Shepherd knew Lucie, her deep feelings for Frances and Elfie, and how much these children meant to them, so off Lucie went across the Atlantic with two young children. The christening was beautifully documented in a formal photo and must have meant a great deal to the aunts.

1915: World War I

Patricia Wilderspin Franz, Lucie and Shepherd’s third daughter, was born on July 12, 1915, in Washington, DC. The family was complete with three girls.

Letters continued to flow back and forth across the Atlantic, bringing perspectives on World War I, now a year in progress. Shepherd and Lucie, living in the capital, felt the tension of war and the different opinions toward it. President Woodrow Wilson was keeping the United States as a neutral and independent power to broker peace. The American public, along with many European immigrants, were of many minds. There were those who were adamant the country should enter the war, but pacifism had strong support from the Protestant church in America and the growing women’s movement.

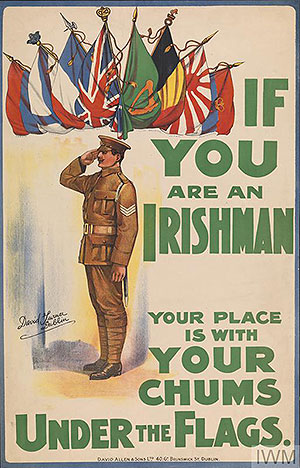

Elfie wrote that in Ireland, Irish Catholic boys and men were enlisting. Many signed up to have a paying job or for the chance at overseas adventure, or what she feared would be misadventure. Some Anglo-Irish Protestants were also joining the fight, wishing to support the British, whom they continued to view as their protectors. The two groups were kept in separate regiments. Irish Catholic troops made up the Sixteenth Division, while the Thirty-Sixth was Anglo-Irish Protestant. Elfie considered the separation a shameful apartheid. As she and many others feared, the Irish Division was treated poorly by the British, adding more aguish to an already troubled society and further dividing the people of Ireland.

1916: The Easter Rising

In early 1916 final planning was in motion for the ill-fated Irish rebellion that became known as the Easter Rising. It was veiled in secrecy and scheduled for the twenty-fourth of April by the leadership of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and Cumann na mBan, the Irish women’s paramilitary.

Most Anglo-Irish were unaware of the coming rebellion, so it would have been of no immediate concern in the Young home. Thomas was gone, the school had closed in 1901, and the aunts were rattling around in the big house, tending to their own business.

Frances and Elfie must have been startled to read newspaper accounts of the Rising that had taken place so close to them. How had they been unaware, as were many Anglo-Irish and Irish, of this rebellion? The rebels had done a good job of keeping their secret, but had been tragically overwhelmed by British troops. An estimated 1,800 Irish volunteers were seized at the General Post Office in Dublin and other major buildings. All this was within a few miles of the Youngs’ home, yet they learned of it after the fact. The rebels had held out for five bloody days before accepting the futility of their cause and surrendering to the British. Irishmen fought on both sides, and some five hundred people were killed, mostly civilians tragically caught in the crossfire. The public executions that followed left wounds in the Irish soul and psyche that would never heal.

An intriguing historical discovery occurred while my husband and I were in Dublin in 2016 as Ireland was celebrating the centennial of the 1916 Easter Rising. As we were walking in the Youngs’ Rathmines neighborhood—Holy Trinity Church, with its sky-blue door, still standing in the middle of Belgrave Road—my husband spied a shiny new plaque that had been placed on a house few doors from where the Youngs lived. It read:

Dublin City Council

Dr. Kathleen Lynn

1874–1955

Lived here from 1903–1955

Physician and feminist

Surgeon General, Irish Citizens Army

Co-Founder St. Ultan’s Children’s Hospital

Commanded City Hall Garrison, 1916 Rising

Following the deaths of Sean Connolly and Sean O’Reilly

Kathleen Lynn had lived at #9 Belgrave, and the Youngs lived at #14! This happenstance finding brought the Rising alive for us in the context of the Youngs.

At the time, history of the rebellion only recorded the actions and leadership of the men involved. Lynn’s bold role was illuminated much later when a historian, Margaret Ó hÓgartaigh, wrote Kathleen’s biography, Kathleen Lynn, Irishwoman, Patriot, Doctor, published in 2006. In Kathleen’s reminiscences of April 1916, during Holy Week before Easter, she wrote, “On a moonless night, I went out with the car to St Edna’s [Irish-language school established by nationalist leader Padraig Pearse] where the guys loaded it with ammunition and put theatrical stuff on top of it. Hoping to get through [British blockades] Willie Pearse [Padraig’s brother] brought it in with me and landed it safely in Liberty Hall where there were many willing hands to unload it.”

Ammunition and gun running! It was also revealed that Kathleen’s basement on Belgrave Road was used to store ammunition. No wonder their street was called “Revolutionary Road” by the underground. The aunts, unbeknownst to them, were living next to an ammunition dump!

How I wish I knew if the aunts had known Kathleen! Nonetheless, this discovery was remarkable and fired my imagination.

1920

This takes us to 1920, when our story begins, when Lucie received the telegram telling her of Elfie’s death. They were all gone.

She left her girls with Shepherd, a nanny, and a housekeeper who took them for the summer months to the coast at Shady Side, Maryland, traveling there on the Emma Giles, a steam paddle wheeler. Shepherd joined them when he could. At the end of summer, the girls returned to their home at St. Elizabeths to start the fall semester in their District of Columbia schools.

March 1921

Lucie closed the door on RockView for the last time and handed the keys to her solicitor’s assistant in March 1921. A month earlier Lucie had received a letter from Shepherd wondering just when she planned to come home. The girls missed her and so did he. He was teaching physiology part time at George Washington University. His position at St. Elizabeths had changed when research shifted focus from the neurological and physiological to the psychoanalytic study introduced by Sigmund Freud. He was also busy with a six-month course at the Bureau of Veterans Affairs in neuropsychiatry. She needed to come home.

She missed her family, too. She had been in Dublin for almost a year, sorting papers, finding bank books, settling accounts, trying to decide what to have shipped to America and what to give away, and visiting with her many friends. It was like sifting through their lives, and frequent social distractions were most welcome. Frances, Alfreda, and Thomas had lots of room in their old house, and they had kept everything.

The day after Lucie received her husband’s letter, she called a shipping firm. A team of workers arrived by the end of the week and began packing up the house. In the end, the things she had not cleaned out—letters, glasses, pencils, pens, prayer books, books, Bibles—in bedside tables were all left as is, the drawers full. She marked and piled the pieces she wanted sent: desks, dressers, tables, chairs, paintings, books, silver, dishes . . . There were so many memories in these objects, she could not leave them behind. They were her history.

I have the handwritten ship’s manifest, listing each piece in the shipment, thankfully sparing us the contents of the drawers. Lucie was sure she would have time for the small things when she got home, or so she thought. Everything went to Washington, DC, where many of Thomas’s paintings were hung, furniture was arranged, and coveted objects found places in their home. Drawers were eventually emptied into boxes and stored for later examination. It is in these dumped-in boxes that I found a collection of their lives, the material that inspired Whispers.

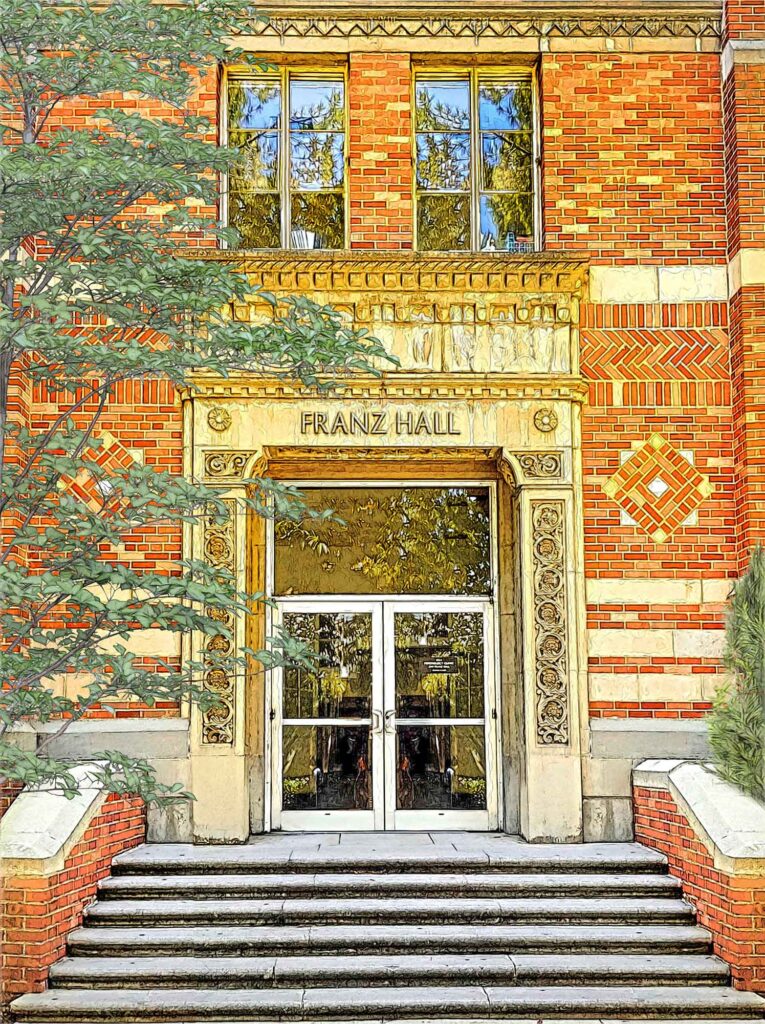

Lucie, Shepherd, and UCLA

Lucie’s life took a fortunate turn in 1924, when Shepherd became a professor and the first department chair at the new psychology department at the University of California, Los Angeles. They moved across the country to California. The campus started in downtown Los Angeles, and the Franz family made their new home at 1857 Kingsley Ave. When UCLA outgrew the downtown campus and moved to Westwood, where it remains today, Lucie and Shepherd bought a large Spanish-style home on Levering Avenue in Westwood. It became well known as a campus social center for faculty, students, and academic visitors who flocked to Lucie’s generous hospitality and Shepherd’s warm welcome. The professor was famous, but Lucie was the magnet. Their open-door policy was in full force. Shepherd was a smoker and kept his desk in the living room, where he smoked and worked as my grandmother entertained around him.

Shepherd Ivory Franz’s distinguished career held the beginnings of the blossoming field of neuropsychology. As head of the department at UCLA, he attracted talented faculty and students and built a solid reputation for his field. He died of ALS October 14, 1933. When a new psychology building was built at UCLA in 1950, with an inverted fountain out in front, it was named Franz Hall.

Many of the boxes shipped in 1921 were never opened and, when Lucie died, they went into her daughters’ garages. The furniture, silver, dishes, and paintings are distributed among Lucie’s grandchildren today, but few in the next generation know the story of this bounty of their personal history. I received my share and took everything that no one else wanted. My exploration began about eight years later, when I started opening boxes . . .

Thomas, Eliza, and James

Thomas died on March 20, 1901, less than two months after his ninetieth birthday celebration. He was buried beside his wife, Sarah, and their children in Mount Jerome cemetery, Dublin. Frances and Elfie are also buried there. Lucie’s father, James Simpson Niven, died a revered member of the community in London, Ontario, in 1916.

Lucie came to live with us after my mother came out of the TB sanitarium. She died in 1949 while living with my parents, Betty and Yngve Ahlm; my brother, Shepherd; and me. The night before she died, unexpectedly from a heart attack, she cooked food for the family to eat while she was away, packed her bag, and planned to take the Southern Pacific “night owl” the following evening to San Francisco to visit friends. She would have loved this story because she liked a good ending. I can hear her saying, “I just caught the wrong train.”

Lucie’s Legacy

Granny Lucie, your story has been told for you, placing you and yours in time and history. I hope the tale will give life to the many personal treasures you brought across the ocean to America that will continue to be disbursed in our family, as the generations multiply.

You were an authentic person who embraced each of us and took life as it came, with a light touch. Your gifts to us were many: you taught us to laugh at life and ourselves, read for pleasure, enjoy the communion of food and drink, and tell stories as a powerful part of family and friendship. You taught us by example the pattern for passing on a human legacy, stories told around the hearth and table, as old as time. We have these deep yet simple tools ingrained in us. As a result, we know how to keep the thread of past lives with us, through story and imagination. In the end we see our lives painted on a larger canvas, reaching back as we move forward.

Christina Holloway, 2020